In 1887 while studying, Czech painter and decorative artist, Alphonse Mucha (1860 – 1939) moved to Paris. There he, in addition to studying, worked at producing magazine and advertising illustrations. About Christmas 1894, Mucha happened to go into a print shop where there was a sudden and unexpected need for a new advertising poster for a play featuring Sarah Bernhardt. Mucha volunteered to produce a lithographed poster within two weeks, and on 1 January 1895, the advertisement for the play Gismonda by Victorien Sardou was posted in the city, where it attracted much attention. Bernhardt was so satisfied with the success of this first poster that she began a six-year contract with Mucha. His style was given international exposure by the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris, of which Mucha said:

“I think [the Exposition Universelle] made some contribution toward bringing aesthetic values into arts and crafts.”

Mucha produced a flurry of paintings, posters, advertisements, and book illustrations, as well as designs for jewelry, carpets, wallpaper, and theatre sets in what was termed initially The Mucha Style but became known as Art Nouveau (French for “new art”). Mucha’s works frequently featured beautiful young women in flowing, vaguely Neoclassical-looking robes, often surrounded by lush flowers which sometimes formed halos behind their heads. In contrast with contemporary poster makers he used pale pastel colors.

Mucha’s work has continued to experience periodic revivals of interest for illustrators and artists. Interest in hiss distinctive style experienced a strong revival during the 1960s, with a general interest in all things Art Nouveau.

Alphonse Mucha, Study for a Decorative Panel, 1908 via

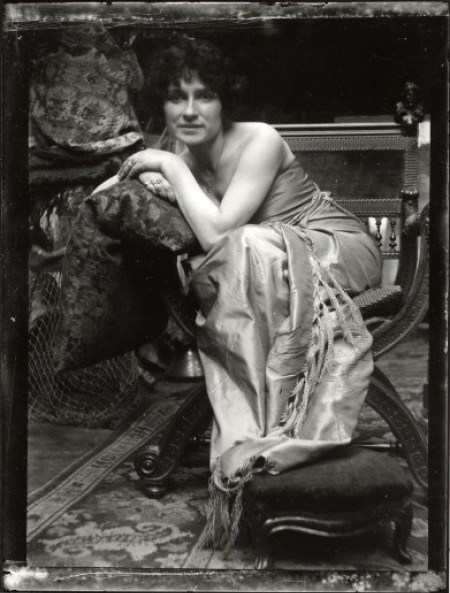

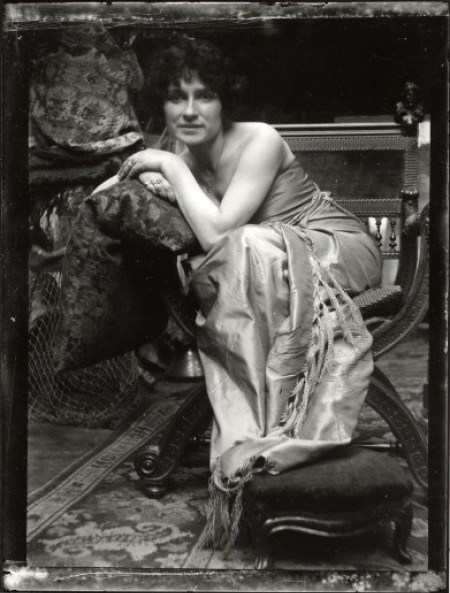

Alphonse Marie Mucha. Model posing in Mucha’s studio rue du Val de Grâce © Mucha Foundation via

Alphonse Mucha. Model posing in Mucha’s studio rue du Val de Grâce © Mucha Trust

via

Alphonse Marie Mucha. Model posing in Mucha’s studio rue du Val de Grâce via

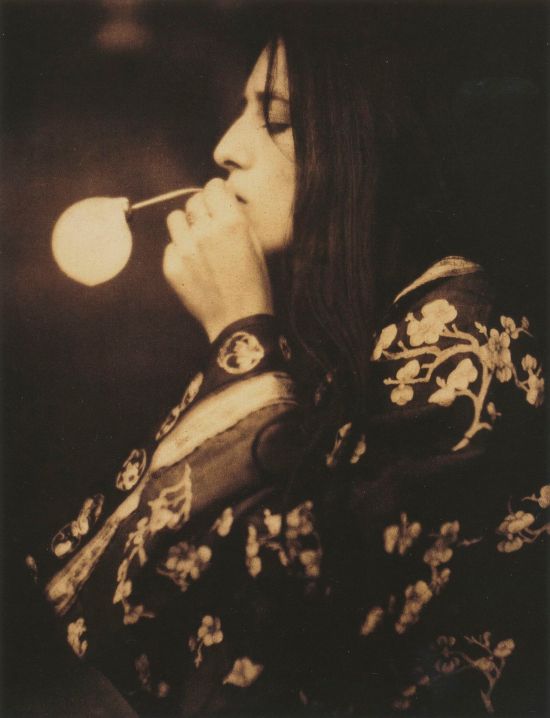

The Precious Stones photographic study in Mucha’s stdio Rue du Val de Grâce, 1900, Paris © Mucha Trust via

Portrait of a Lady photographic study in Mucha’s studio, Rue du Val de Grâce, ca. 1900, Paris © Mucha Trust via

Photographic study © Alphonse Mucha Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris via

Photographic study for ‘Truth’ © Alphonse Mucha Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris via